As the candle flickers, a pair of pursed lips politely opens the door for a hesitant smile. Phantom Thread opens with a premonition: those whom we vow to go to the grave with will always have been our most demanding companions.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest project is about love. It is true to the trope; beautiful, chaotic, ambivalent, yet the trope is put under the knife so that something informative emerges, and its two main characters: Reynolds and Alma, are subjected to the very same knife.

Reynolds Woodcock, a dressmaker for the post-war aristocracy of England is a man cocooned by his web of habits. He lives with precision and is willing to sacrifice a great many things for this; he forgoes spontaneity, he forgoes love. He repeats his routine every day, slowly treading a path, stamping out things that would grow in place of his meticulously arranged schedule. Reynolds is the head of a well-resourced house, and like many rich boys is privy to spitting the dummy the moment things veer from expectations.

Alma is the counterpoint to this. She is introduced in a hotel breakfast, literally stumbling into the frame. She takes his order, he commands her, we see that she is malleable, Reynolds asks her to dinner.

To be malleable is important for Paul Thomas Anderson, for the most part of the movie we will see Reynolds so greedily shape Alma into several shapes, yet recoil in horror the moment she attempts to reciprocate this. This is the core of the film, it is not a film about romance. It is a film about love, and for Anderson, love is a violent, invasive, testing phenomenon. What is presented to us is not a bourgeois fairytale, but two sculptors carving deep into each other in order to craft something beautiful and immortal.

We are introduced, with a screech and a thud, to Cyril, the strong-headed sister of Reynolds. Immediately it appears that she is a female competitor for Reynolds attention. However, as the film develops we gain the sense that she is an externalisation of Reynolds, she affirms his behaviours. Her role isn’t static though, she shifts and challenges both him and Alma; perhaps this is what he refers to in calling her “my old so-and-so.”

Both Alma and Reynolds have respective turning points, at which they surrender themselves to the will of their partner and do something that conflicts with their core values. For Alma, this happens early in the film, as she strips the pitiful, drunk and depressed Barbara Rose of her coveted Woodcock dress. From here on out, recognising that she has made her sacrifice for the pair, she expects the gesture to be reciprocated.

She tries to force Reynolds into this twice, firstly through surprising him with dinner, to which he responds aggressively like a child, upset and cornered. He lambasts her for cooking his asparagus in butter rather than olive oil, insults her, childishly encircles her with stupid questions: “have you got a gun? Are you here to kill me?”. The dinner ends in tears. Alma moves to coercion.

She poisons him, grinding up toxic field mushrooms and scattering them into his tea. The effect is debilitating. Gravely ill, Reynolds becomes unable to work. His social web, his habits, everything that tethers him to this world as Reynolds Woodcock is broken down. Near death, he is able to see the care his family bestow him. He is able to see in Alma a carer (despite unknowingly succumbing to her poison) and is able to rebuild life having relinquished his obsessive control over it. Here Reynolds is finally malleable, able to be bent into a shape that better fits the two.

He recovers and immediately marries Alma. But before he asks for her hand he says something very important: “A house that never changes is a dead house.” This is the central thesis of the film, that the opposite of this aggravating process of change is stagnation.

Cyril represents a medium between Reynolds childish urges and his role as an actor within a social web, and in a way, is a water diviner for the love that grows between the pair. As Alma challenges him and asserts her place within the house, Cyril’ds receptiveness towards her shifts. As Alma becomes more brazen, Cyril’s position as a source of consensus begins to turn against Reynolds. In one scene towards the end we see her authority as she responds to an attack from her brother: “Don’t pick a fight with me, you won’t come out alive. I’ll go right through you and it will be you who ends up on the floor. Understood?”

Why did this conversation occur? Hadn’t the marriage solidified all the progress the pair have made? Anderson makes it clear that something key is yet to be done. This manipulation was not offered up like Alma’s was, it was forced upon Reynolds. As the marriage slowly begins to deteriorate, we understand that this needs to occur.

The French philosopher Alain Badiou writes of a ‘two-scene’ the view of the world unique to couples that have endured together both time and experience. We begin alone, both with our own preconceptions of the world, and as we get to know another as we know ourselves we begin to change, it is as if we destroy the old person and replace it with one that exists alongside another. In the two scene, one views the world from their own perspective, and from the perspective of a halve in a unit. This is an extraordinary, uniquely human experience, but it requires the relinquishing of complete independence, it requires the relearning of modes of living. This can be extremely painful (Badiou describes it as a destruction of the former self), and Anderson uses the act of consuming poison to reflect this consummation of the two-scene.

…..

Across the fading darkness stands Alma, holding a mushroom as the candlelight licks her shoulders. The pan hisses and the air is thick with butter and egg. A wry smile, a creased brow, a shiver, a tightened jaw. On the table, an omelet is placed neatly. Reynolds is given silence, a cue to let him know that he is about to make an important decision.

The knife screeches against the porcelain plate, and from it, one single bite of omelet is procured. Almas gaze forces Reynolds’ hand, he takes the bite. There is a mutual understanding that this bite signifies a desire to be shaped, to have no control, to rely on trust.

Almas lips part: “I want you flat on your back. Helpless, tender, open, with only me to help. And then I want you strong again.”

When the first bite of poison has been swallowed, they share a smile. The first of many from hereon.

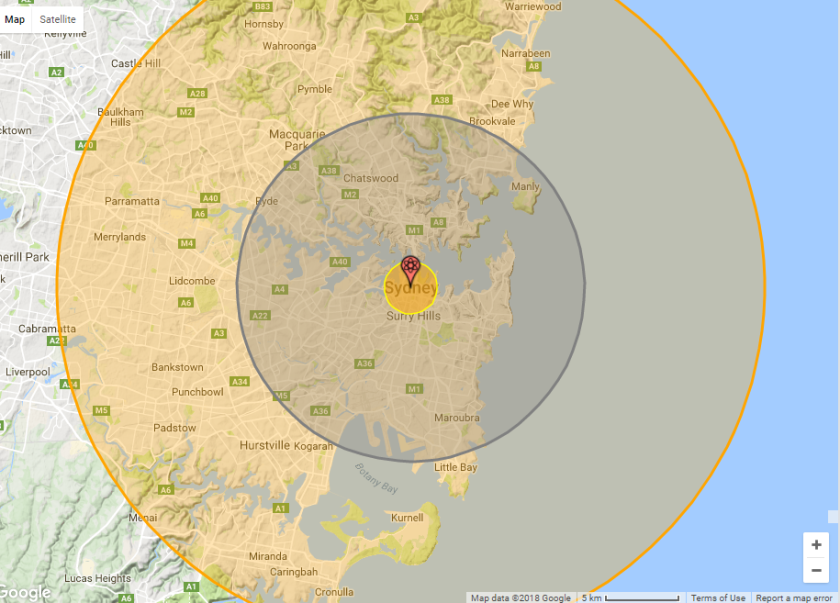

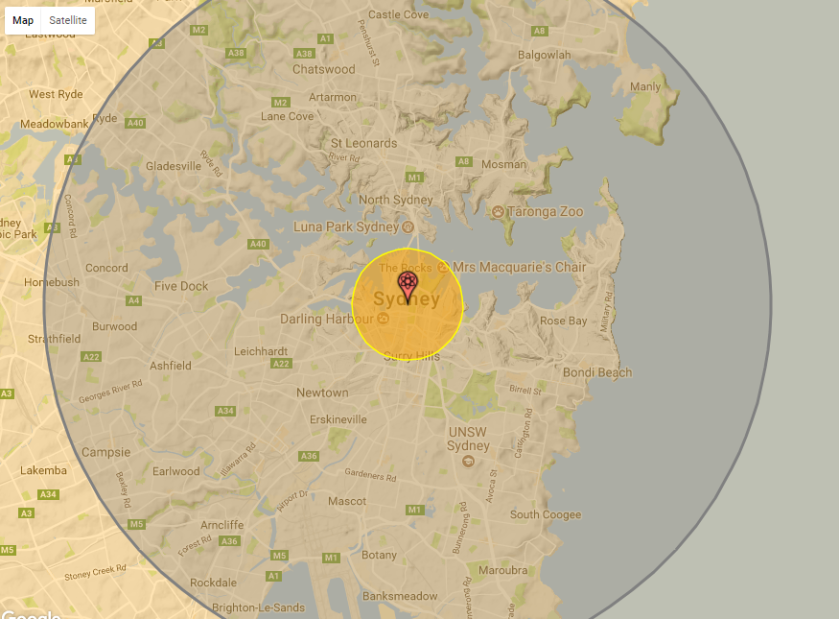

The yellow radius represents the size of the fireball the explosion will produce, where temperatures have been measured to read hotter than the surface of the sun. 10.6 Square Kilometers of Sydney will be instantly vaporised. Long before we can even settle the debate as to which is the oldest, Australia’s first pub will disintegrate into radioactive dust that will enter the stratosphere and fall somewhere on the eastern coast, as far up as Yamba and Byron bay.

The yellow radius represents the size of the fireball the explosion will produce, where temperatures have been measured to read hotter than the surface of the sun. 10.6 Square Kilometers of Sydney will be instantly vaporised. Long before we can even settle the debate as to which is the oldest, Australia’s first pub will disintegrate into radioactive dust that will enter the stratosphere and fall somewhere on the eastern coast, as far up as Yamba and Byron bay. Perhaps you just saved for a ridiculously overpriced apartment in Strathfield, don’t stress the enormous debt you just incurred. Strathfield’s buildings, like most buildings within the blue zone, will crumble from the shock waves, especially if they’re built by Meriton. You will most likely die instantly from the shock within this area, if not the heat from the blast is effectively guaranteed to kill you and your landlord. With most cars now destroyed and their drivers dead, the roads would be clogged, emergency services would have a tough time reaching any survivors, although Parramatta road would still effectively be the same to drive on.

Perhaps you just saved for a ridiculously overpriced apartment in Strathfield, don’t stress the enormous debt you just incurred. Strathfield’s buildings, like most buildings within the blue zone, will crumble from the shock waves, especially if they’re built by Meriton. You will most likely die instantly from the shock within this area, if not the heat from the blast is effectively guaranteed to kill you and your landlord. With most cars now destroyed and their drivers dead, the roads would be clogged, emergency services would have a tough time reaching any survivors, although Parramatta road would still effectively be the same to drive on.